Food Choice, the Psychology of Decision Making, & Cognitive Biases in Decision Making

We may not always realise it, but we make countless food decisions every day, from choosing a midday snack to planning an evening meal for the family. While these choices can seem routine, two major reviews, “The Self-Control of Eating” (Tomiyama, 2024) and “Predictors of Food Decision Making: A Systematic Interdisciplinary Mapping (SIM) Review” (Alm et al., 2017), reveal that our food choices are the result of highly complex processes. Psychological biases, environmental influences, habit loops, and even social pressures all play pivotal roles.

Despite the simplicity of “just eat better” messages, the reality is more nuanced. Many of us juggle multiple demands, work stress, family obligations, or a tight budget, and in these everyday moments, we’re nudged by cues and cravings we rarely notice in the moment. Understanding what science has discovered about decision-making can help us create healthier, more satisfying eating patterns without excessive reliance on willpower alone.

In this blog post, we’ll discuss how cognitive biases shape eating behaviour, why the environment matters so deeply, how self-control both helps and occasionally hinders, and which practical strategies you can adopt to feel more confident and mindful about your daily food decisions. Our goal is to provide evidence-based suggestions that set you up for long-term nourishment, physically and psychologically.

Why Food Choices Feel Hard: A Psychology of Decision Making view

Both The Self-Control of Eating (Tomiyama, 2024) and the SIM review by Alm et al. (2017) emphasise that food choices are rarely dictated by rational thinking alone. Instead, they emerge from an intricate blend of personal preferences, learned habits, and immediate contextual cues. Here are just a few factors:

Overabundant Options

In many Western societies, especially, food is accessible in near-limitless varieties. From takeaways to novel snack offerings, choice overload can be a real issue. When a person is tired or stressed, defaulting to quick, easily available meals can feel like the most convenient solution.

Conflicting Goals

Eating decisions reflect deeper goals, like maintaining a healthy weight, saving money, or simply indulging for pleasure. It’s normal to vacillate between these impulses (e.g., “I want to eat more vegetables” vs. “I deserve a treat”).

Emotional and Social Influences

Research shows stressors can make us crave calorie-dense snacks, while social gatherings, office parties, and birthday celebrations often encourage indulgence. Aligning these moments with longer-term health aims can prove tricky.

According to a recent review in Frontiers in Nutrition, eating is often guided by reinforcement learning, with both Pavlovian and goal-directed mechanisms at play frontiersin.org. These neural systems reward us for indulging (makes us feel good briefly) or for making conscious, value-based decisions. But balancing these processes is difficult in an environment saturated with cues promoting “just one more bite.”

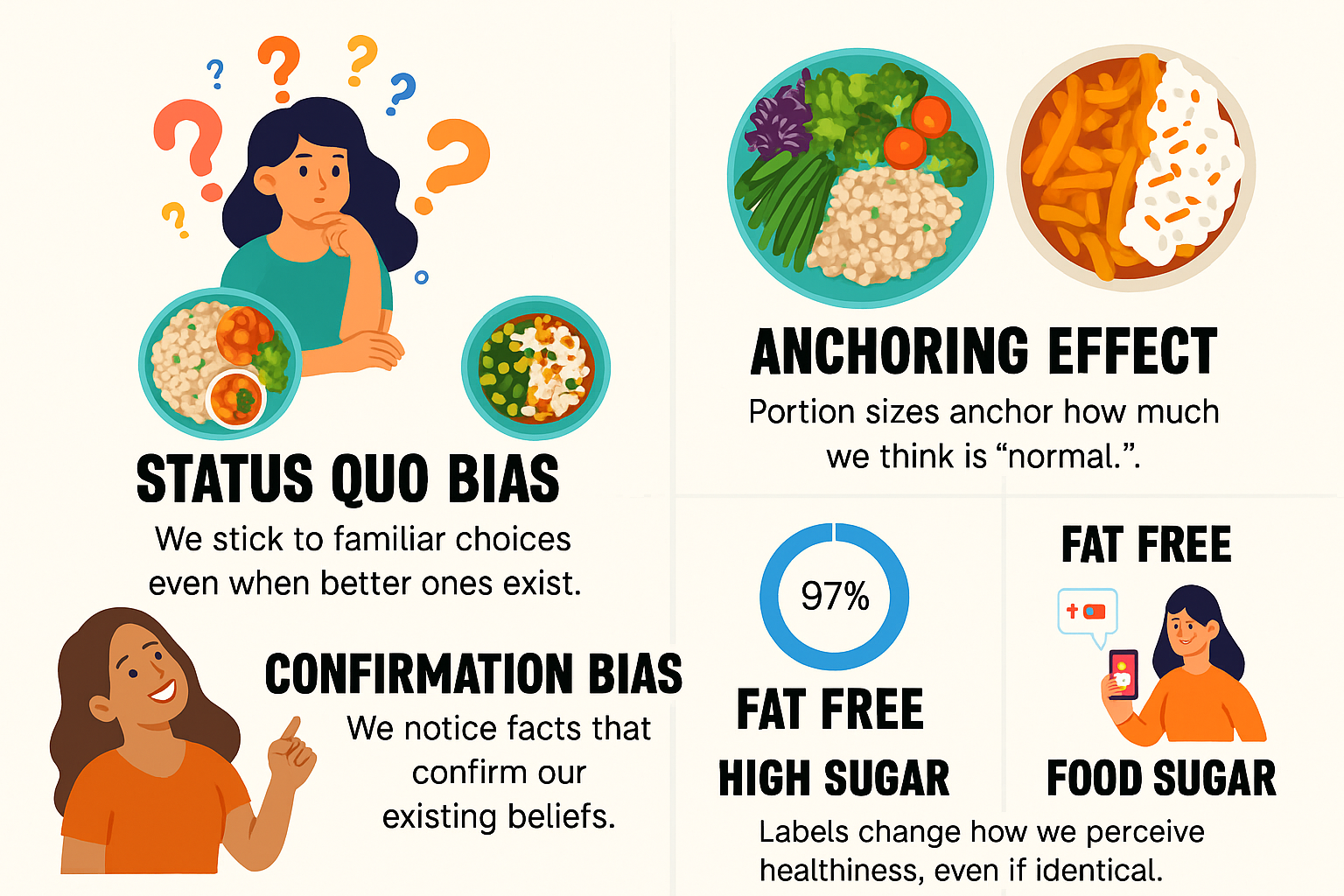

Cognitive Biases in Decision Making that disrupt healthier choices

When we speak of “cognitive biases in decision making,” we’re talking about systematic mental shortcuts that can lead to less-than-optimal choices. While biases help us make quick decisions in daily life, they can also sabotage healthy eating intentions.

Status Quo Bias

We often gravitate to whatever is familiar, whether it’s a favourite takeaway on a Friday night or that same chocolate bar in the shop queue. This preference for the status quo means we tend to keep repeating habits, even when we know healthier alternatives exist.

Anchoring Effect

The first piece of information we see (e.g., a large portion size displayed on the menu) can “anchor” our sense of what a “normal” portion should be. Consequently, if a restaurant’s standard portion is large, we unconsciously follow that lead, consuming more than we might intend.

Confirmation Bias

If you believe “healthy eating is annoyingly expensive,” you might pay more attention to pricey organic produce and overlook budget-friendly, nutrient-rich tinned items. This can reinforce the perception that a healthier diet is out of reach, even if evidence suggests otherwise.

Framing Effects

Food labels, marketing claims, or even the presence of green and red iconography can shape how we assess a food’s healthfulness. For instance, being told something is “97% fat-free” often makes us feel better about it, even if the sugar content is extremely high.

Putting it all together, biases can subtly guide day-to-day decisions. Recognising them is the first step. Next, a shift in perspective can help mitigate them. For instance, if you know you commonly choose the largest portion available (the anchoring effect), you can actively opt for a smaller portion or share a dish with someone else. These micro-choices add up.

Environmental Forces You Might Overlook

In her review of self-control, Tomiyama (2024) points out that a major obstacle to healthy eating is the “obesogenic” environment one replete with ultra-processed foods, large portion sizes, and constant reminders to grab a quick bite on the go, whether from the petrol station or a snack machine at work. Meanwhile, the SIM review by Alm et al. (2017) reveals that the abundance of cheap, palatable foods is a significant driver in setting dietary patterns.

Food Accessibility

The simplest way to control your consumption is to control your environment. If chocolate biscuits are in plain view on the kitchen table, you’re more likely to indulge. Conversely, stocking your fridge with washed, cut vegetables at the front can lead to more mindful snacking.

Portion Distortion

Over the past few decades, portion sizes in restaurants and packaged foods have steadily grown mdpi-res.com. Larger plates, cups, and bowls all encourage us to consume more. This phenomenon, sometimes termed portion distortion, can be addressed simply by using smaller dinnerware.

Social Modelling

Evidence suggests that when we dine with others, friends, family, or colleagues, we unconsciously mirror their eating habits. If they eat more, we eat more; if they gravitate to certain items, we follow suit mdpi-res.com. Recognising and gently adjusting these social patterns can help, for example, by deciding on healthier group options or featuring more vegetables at a shared meal.

Cultural Nudges

Certain cultures celebrate food abundance; refusing a second helping might be seen as impolite. In others, ready-to-eat convenience meals lurk on every corner. Understanding your cultural background and environment can empower you to make conscious decisions that align with your personal health values, rather than reacting to external norms.

Self-Control: Helpful but Not Always Sufficient

The Self-Control of Eating by Tomiyama (2024) concedes that self-control, while useful, is often overused in public health messaging. Telling individuals to simply “resist temptation” does not always work when living in an environment saturated with enticing junk food. This supports the notion that self-control can be depleted by stress, fatigue, or negative emotion, leading to the familiar “what-the-hell effect” when diets break down.

Ego Depletion Controversy

Early research posited that willpower behaves like a muscle that tires with use, but more recent findings question this simplistic perspective. The actual scenario is likely more nuanced; self-control can be influenced by mindset, blood glucose, or habit strength.

Identity-Oriented Approaches

One powerful alternative is identity-based eating, where you think of yourself as a “person who prioritises fresh, nutrient-dense foods.” This approach focuses on reshaping how you see yourself rather than mustering continuous willpower. For instance, if you identify as someone who loves colourful salads or local produce, you’re more likely to select them automatically.

Value-Based Decisions

The new wave of behavioural research emphasises aligning your eating choices with personal values (like sustainability, social justice, or longevity) frontiersin.org. By keeping these higher values top of mind, short-term impulses (e.g., grabbing a doughnut simply because it’s there) diminish in appeal.

Ultimately, self-control is part of the toolkit, but not the only tool. Building supportive environments, forming identity-driven habits, and reducing friction in making healthier choices all matter deeply.

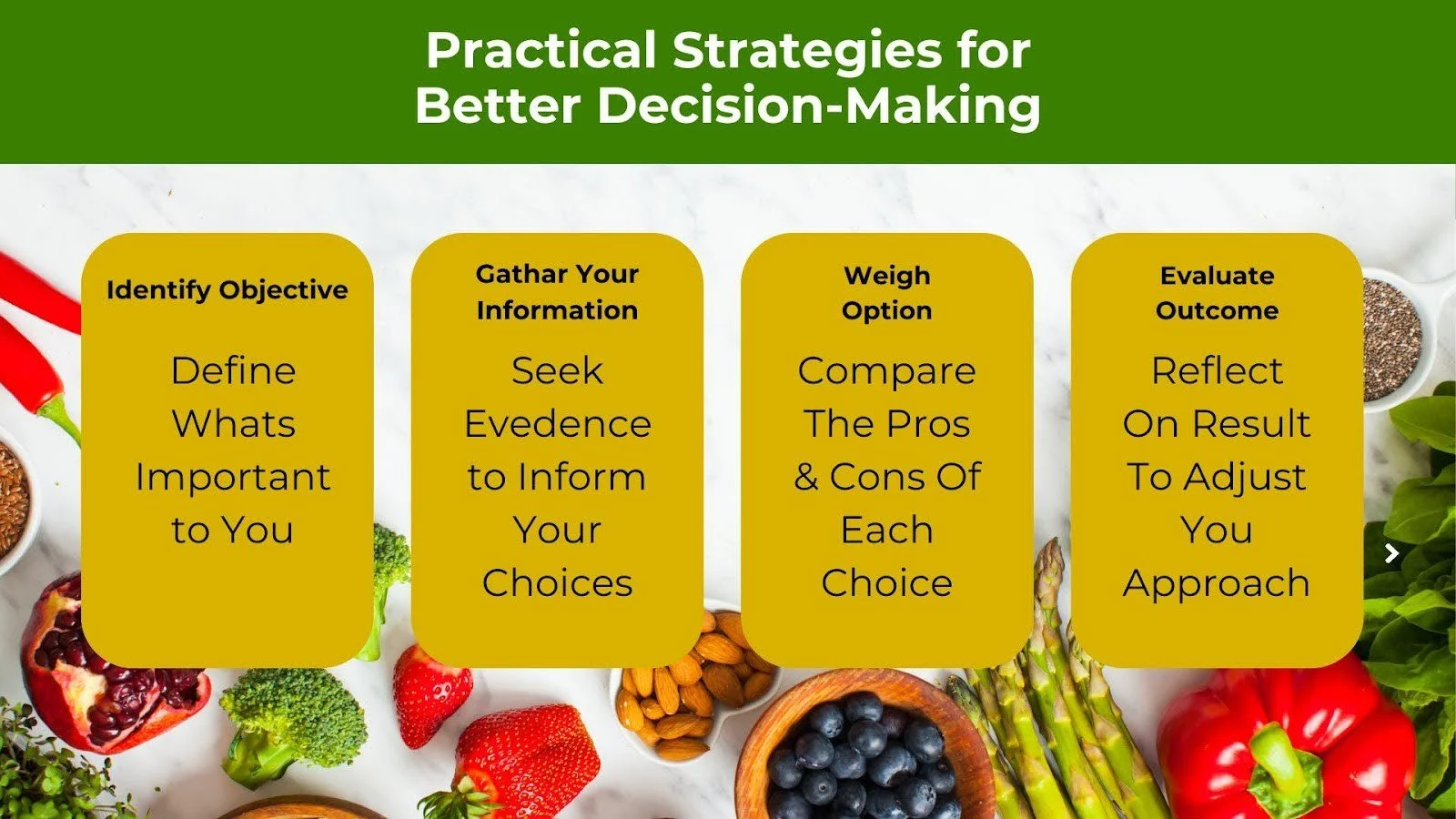

Practical Strategies for Better Decision-Making

Embracing the science of decision-making needn’t be complicated. Below are a few straightforward strategies to nurture healthier eating patterns without over-relying on forced willpower:

Adjust Your Food Environment

Clear Visibility: Keep your healthiest foods in clear containers at the front of your fridge. Stash sweets or crisps in a less accessible spot.

Smaller Portions: Pre-portion treats into single-serving containers or use smaller plates to naturally regulate quantity.

Home Cooking: As often as possible, cook at home in batches; controlling the ingredients will help you bypass hidden additives or extra saltz.

Use If-Then Plans: Adopt a strategy such as “If I feel hungry between meals, then I’ll go for fruit or nuts first.” Having these adaptive responses in place can help you avoid impulsivity, particularly when you’re stressed or time-pressed.

Reframe Your Identity: Self-Description: Remind yourself, “I’m someone who values balanced meals.” Over time, this identity shift influences behaviour more sustainably than pushing yourself with rules.

Values Alignment: If environmentalism is important to you, focus on plant-rich meals and local produce. If you care about cultural traditions, adapt family recipes with nourishing twists.

Plan for Social Settings: Offer to Bring a Dish: If heading to a social event, bring something nutritious yet flavourful, like a vegetable-packed salad with a vibrant dressing. This ensures there is at least one healthful option present.

Social Cues: If you know you mimic others’ eating patterns, ask a close friend to support you in choosing more sensible portions or skipping that extra dessert.

Mindful Eating Techniques

Slow Down: Chew each bite thoroughly and place utensils down between bites. This helps you tune into satiety signals.

Sensory Awareness: Pay attention to textures, aromas, and flavours to enhance satisfaction. This approach often leads to eating less but enjoying it more.

Emotional Check-In: Before reaching for a snack, ask, “Am I physically hungry, or am I bored or anxious?” If you realise it’s stress, try a walk or a quick stretch instead.

Does Information Alone Lead to Behaviour Change?

Traditional nutrition campaigns often bombard us with facts, figures, and warnings about what foods we “should” avoid. On the surface, education seems key; after all, it’s essential to understand what is in your meal. However, purely rational messages like “eat fewer calories” or “choose whole grains” are frequently overshadowed by subconscious biases, social triggers, and emotional states.

• Emotional vs. Rational Brain

Numerous social psychology studies have consistently shown that choices related to food depend greatly on immediate emotional states mdpi-res.com. Even if you “know” your best option, you may still crave a sugar-laden energy drink under stress.

• Shortcomings of Education-First Approaches

While nutritional knowledge remains valuable, knowledge alone does not always translate into action. That’s precisely why The Self-Control of Eating article by Tomiyama (2024) advocates shifting from personal willpower narratives to broader changes in environment and identity.

• Building Skills, Not Just Knowledge

Instead of purely listing healthy vs. unhealthy foods, we might do better by teaching cooking skills, meal-planning tactics, and stress-management strategies. These real-life skills help people integrate healthier eating in day-to-day life.

Lessons from Interdisciplinary Research

The SIM review by Alm et al. (2017) mapped out ways different fields, like public health, psychology, marketing, and behavioural economics, study food decisions. One key takeaway is that rarely do these disciplines collaborate deeply. As a result, interventions tend to focus on one piece of the puzzle (calorie control, for instance, or marketing analysis) rather than the full tapestry, which includes emotional states, culture, environment, and social norms.

• Bridging Gaps for Real-Life Impact

Integrating diverse frameworks allows for more nuanced solutions. For example, combining public health guidelines with insights from behavioural economics (like “nudges” that make healthy items more prominent on menus) can spark meaningful, wide-reaching changes.

• Need for Complex Models

A single model or formula cannot capture all the factors shaping food decisions. As the review underscores, a more complex view , encompassing taste perception, personal identity, emotional cues, and convenience , increases the likelihood of successful interventions sciencedirect.com.

• Evolving Public Policies

Recognising that healthy eating is not solely a matter of personal willpower suggests governments and food industries could share responsibility. For instance, retailers could adjust product placements, while policymakers could encourage portion-size guidelines and transparent labelling.

Conclusion: Empower Yourself with Healthy (and Realistic) Choices

When it comes to daily food choices, we’re neither fully rational nor entirely at the mercy of cravings. We operate in a “push-pull” environment where cravings, identities, social norms, and convenience all converge. As The Self-Control of Eating (Tomiyama, 2024) and the SIM review (Alm et al., 2017) demonstrate, conquering modern food environments calls for more than just knowing what’s healthy.

Key Takeaways:

Acknowledge your biases. Notice when anchoring or the status quo might be steering your choices.

Prioritise environment design. Make the healthy choice the easy choice, at home, in the workplace, and when dining out.

Move beyond willpower. Lean on habits, social support, and identity-based strategies that reduce the burden on day-to-day self-control.

Embrace emotional awareness. Recognize stress triggers and practise mindful eating to separate cravings from genuine hunger.

Seek interdisciplinary insights. If you’re looking to change your diet, consider more than nutrients; explore the cultural, social, and psychological elements, too.

By reimagining your relationship with food, you’re taking vital steps toward lifelong well-being. Small, consistent changes, like portion control or mindful snacking- can make a surprisingly big difference over time. Above all, remember that healthy eating does not have to feel like an endless exercise in willpower. By working with, rather than against, your environment and psychology, you can develop an eating pattern that enhances both physical health and overall life satisfaction.

Ready to apply these insights? Join our free “Mindful Eating Webinar” at Nutrimelab, where we delve deeper into practical tips for busy lifestyles. You’ll learn how to design your surroundings, manage cravings, and build a mindset that supports sustainable, nutritious meals every day.