Risk Perception and Food Decision Making: How Our Brains Weigh the Risks and Benefits

Have you ever caught yourself thinking this while polishing off a bag of crisps or reaching for a second helping of pudding?

For many of us, especially professional women balancing careers, families, and wellness, this kind of inner conflict is all too familiar. You know the risks, but in the moment, something else takes over. And that something is your brain’s risk-perception system.

Understanding how our brains process the risks and benefits of food choices is more than an academic exercise. It’s a key to real, lasting behaviour change, without guilt, shame, or unrealistic rules.

Why It Matters, Especially for Women on the Go

In a world full of nutrition headlines, calorie-counting apps, and wellness influencers, we’re not short on information. What we lack is clarity, and that’s especially true when it comes to how we perceive risk.

Take, for example:

Avoiding bread because of carbs, but drinking wine daily without a second thought.

Thinking one slice of cake will “ruin” your progress, but skipping lunch due to back-to-back meetings seems normal.

Feeling guilty about eating late, but brushing off chronic stress as just part of life.

These examples reveal a mismatch between actual risk and perceived risk, a gap influenced by emotion, social cues, and mental shortcuts. Understanding these patterns isn’t just intellectually interesting, it’s vital for anyone trying to eat more mindfully in the real world.

And for UK-based women in midlife, juggling competing priorities, recognising how you evaluate food decisions can be the difference between all-or-nothing dieting and a sustainable, compassionate approach to eating.

What the Science Says: Judgement, Emotion, and the Brain

In the field of Judgment and Decision Making (JDM), researchers have long studied how people evaluate choices that involve uncertainty, like whether to eat something that’s indulgent but "bad," or skip a meal because of time pressure.

A key paper in this area explains that our brains are not always rational when it comes to food. Instead of calculating objective risks (e.g., nutritional content, long-term health), we’re often swayed by:

Emotional framing (“I’ve been good today,I deserve this”)

Temporal discounting (prioritising immediate gratification over future goals)

Social influence (choosing what others around us are eating, especially in group settings)

These mechanisms help us cope with complexity, but they also create blind spots.

Meanwhile, neuroscience research shows how the prefrontal cortex, responsible for logical thinking and future planning, often takes a backseat when we’re tired, stressed, or emotionally depleted. In these moments, the amygdala , the brain’s emotional centre, takes over, prioritising short-term rewards and downplaying long-term consequences.

In other words: your brain is constantly weighing the perceived risk of a decision, but the scale it uses can shift depending on your mood, energy, and social context.

Practical Tools for Clearer Food Decisions

It’s empowering to know your brain is doing its best, even when it steers you a bit off track. These moments aren’t failures; they’re signals. They tell us our internal systems, stress levels, mental load, emotional state, are calling the shots more than our conscious goals. And that’s human.

With this awareness, we can begin to work with our brains rather than against them. Instead of relying on willpower or harsh rules, we can design gentle nudges that help recalibrate our internal “risk compass” when it comes to eating.

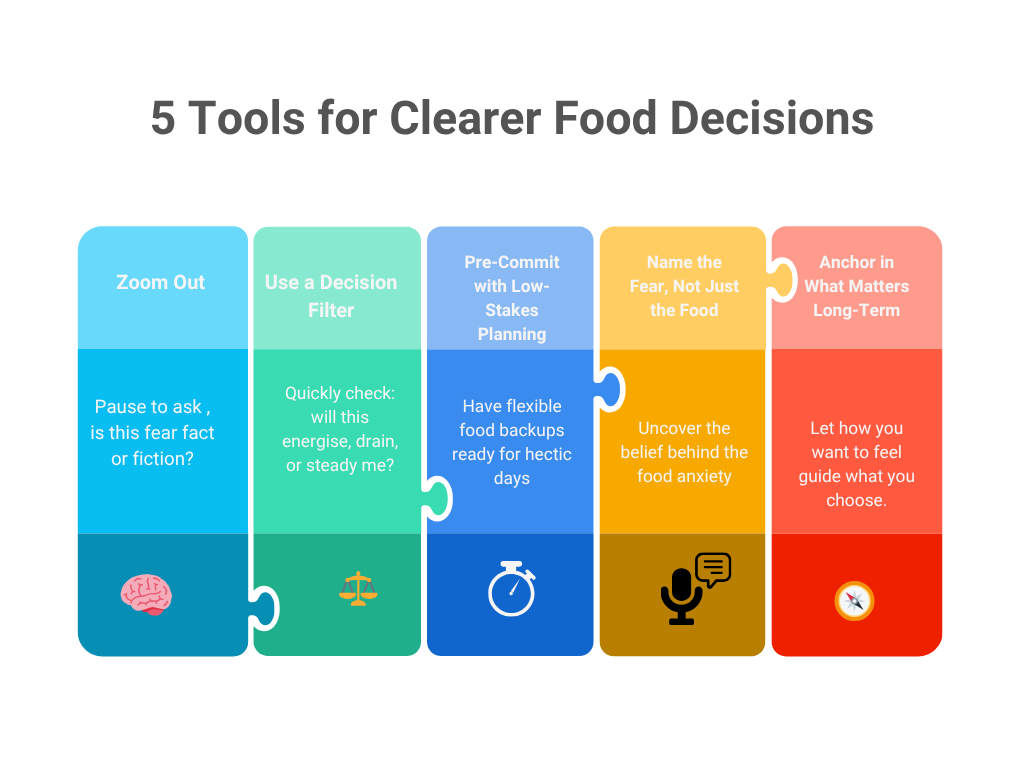

Here are five behaviour-first strategies to support more grounded, nourishing choices, especially on busy, emotionally charged days:

1. Zoom Out: Reframe the Risk

When you find yourself judging a food choice as “good” or “bad,” pause and ask:

“What’s the actual risk here?”

“Am I reacting to a story I’ve heard, or real evidence?”

For example, is eating a slice of toast really harmful, or have you internalised diet culture’s fear of carbs? When you widen the lens, you often find that the perceived danger is rooted in outdated beliefs, not facts.

This shift reduces black-and-white thinking and encourages decisions based on context, not rules. A biscuit during a stressful meeting doesn’t mean you’ve failed, it means you’re coping. The real question is: What do I need right now to feel better long-term?

2. Use a Decision Filter

We make dozens of food-related decisions each day, often without noticing. To interrupt the automatic pattern, introduce a quick mental filter:

“Will this energise me, drain me, or keep me neutral?”

This tiny pause slows reactive choices and gives your prefrontal cortex (your brain’s planning centre) a chance to re-engage.

For example, you might be craving crisps, but after asking this question, you realise what you really need is something satisfying but steady, maybe hummus and oatcakes, or a handful of nuts and an apple.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about choosing with intention, not autopilot.

3. Pre-Commit with Low-Stakes Planning

You don’t need a rigid meal plan. In fact, overly strict rules often backfire. What does help is having flexible go-to options, pre-decided, low-effort meals or snacks that align with how you want to feel.

Example:

“If I’m too tired to cook, I’ll order a sushi bowl or roasted chicken from Sainsbury’s instead of grabbing chips.”

This approach reduces the emotional load at decision points and helps you make better choices even when you’re tired, emotional, or distracted , the moments when risk perception tends to skew most dramatically.

Think of it as setting up a soft landing in advance, not building a cage.

4. Name the Fear, Not Just the Food

Often, we avoid certain foods not because of evidence-based risk, but because of conditioned fears , fears that have been shaped by dieting culture, childhood messages, or social comparison.

Try this:

Write down a food that triggers anxiety (e.g., pasta).

Then write down the fear beneath it (e.g., “I’ll lose control,” “It’ll make me gain weight”).

Now, ask yourself:

“Is this belief serving me , or sabotaging me?”

Naming the fear creates psychological distance. It allows you to question whether the “risk” is real, or simply a relic of unhelpful messaging. Over time, this helps rebuild trust in your own body and instincts.

5. Anchor in What Matters Long-Term

It’s easy to get caught up in calorie math or macros. But lasting behaviour change isn’t fuelled by numbers, it’s driven by meaning.

So ask yourself:

“How do I want to feel, not just right now, but over the week, month, or year?”

Maybe you want to feel energised in the afternoon, clear-headed during meetings, calm around food at social events. Let that be your North Star , not an arbitrary rule or number.

When your decisions are anchored in personal values and desired feelings, risk evaluation becomes more intuitive. You stop seeing every food as a threat or test, and start seeing it as a tool , one that can support, soothe, or energise, depending on the context.

Real-Life Example: Meet Claire from Birmingham

Claire, 38, is a solicitor and mum of one. Her days are long, her schedule unpredictable. She’s been trying to “eat better” for years but often finds herself grabbing pastries or skipping meals, then eating late at night and feeling frustrated.

Through coaching, Claire discovered her real struggle wasn’t knowledge , it was her perception of risk.

She believed eating a sandwich with white bread was worse than not eating lunch at all. But skipping meals left her famished by 7pm, triggering overeating and guilt.

With support, Claire reframed her choices:

She started packing high-protein lunches, even if imperfect.

She let go of black-and-white thinking around food groups.

Most importantly, she stopped labelling herself as “bad” for making spontaneous choices.

Now, she eats more consistently, feels better throughout the day, and no longer panics if dinner isn’t “perfect.”

Frequently Asked Questions:

What is risk perception in food decision making?

Risk perception refers to how we mentally evaluate the potential negative or positive consequences of a food choice. It’s influenced more by emotion and belief than objective facts.

Why do we eat unhealthy foods even when we know the risks?

Because our brain weighs short-term benefits (pleasure, ease, comfort) more heavily than long-term risks, especially under stress or fatigue.

How can I reduce impulsive food decisions?

Try using pause strategies, simple food planning, and environment design (like keeping nourishing snacks visible). These shift the brain from reactive to reflective mode.

Is skipping meals more harmful than eating something imperfect?

Often, yes. Skipping meals can lead to energy crashes, poor concentration, and later overeating, which disrupts both mood and metabolism.

How do social settings affect food risk perception?

We’re strongly influenced by what others are eating. This can override our usual food logic, especially if we want to fit in, avoid judgement, or celebrate.