The Role of Self-Regulation in Food Decision Making: Why We Fail and How to Succeed

From choosing a quick snack between meetings to planning a nutritious family dinner, our daily lives revolve around food decisions, yet many of us struggle to make choices that align with our long-term health goals. Traditional approaches often tell us to “just use willpower,” but this advice overlooks the complexity of modern food environments and the psychological processes underlying our eating behaviours. Recent works, such as “The Self-Control of Eating” by Tomiyama and “Use of Psychology and Behavioral Economics to Promote Healthy Eating” by Roberto and Kawachi, highlight just how intricate (and sometimes fragile) the interplay between personal agency, environment, and decision making can be.

These findings echo a broader consensus within nutritional science, psychology, and behavioural economics: purely rational models of choice fail to capture the realities of our daily eating patterns. Cognitive biases, emotional triggers, environmental cues, and our own self-regulation capacities intersect in ways that can either support or sabotage our best intentions. This blog post explores how decision-making models intersect with self-regulation and why so many of us struggle with controlling our dietary choices. We also offer practical, science-based strategies for building more resilient self-regulation, drawing on key insights from both Tomiyama and Roberto and Kawachi, as well as related research in the field.

Understanding Self-Regulation in Food Choices

Self-regulation, at its simplest, refers to the ability to consciously guide one’s behaviour toward personal goals. In the context of eating, it means aligning day-to-day food decisions with longer-term aspirations, whether those include maintaining a healthy weight, preventing chronic disease, or prioritising sustainable diets. But as emphasised in a concept analysis by Reed et al, self-regulation is influenced by both internal traits (e.g., self-efficacy, emotion management) and external factors (e.g., social context, availability of food).

The “self-control” paradigm, once the dominant lens, tends to reduce these interactions to a matter of personal willpower. Tomiyama observes, however, that this framework overlooks how the modern “obesogenic” environment constantly nudges us to eat more. Vending machines conveniently placed in office hallways, adverts showcasing snacks brimming with sugar, and cultural norms encouraging hearty portions all conspire to make self-regulation an uphill battle. Add to this emotional states like stress, fatigue, and social pressure, and it’s no surprise that many well-intentioned diets fail.

Why We Fail, The Role of Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that help us make quick decisions but often at the expense of rational outcomes. Roberto and Kawachi (2014) [9] highlight the way “status quo bias” and “default effects” can shape our dietary patterns. If a meal deal automatically includes crisps, we may accept it without much thought. Similarly, “anchoring” can affect portion sizes, seeing one large meal option can create the sense that smaller portions are somehow insufficient, even if they provide plenty of calories for our needs.

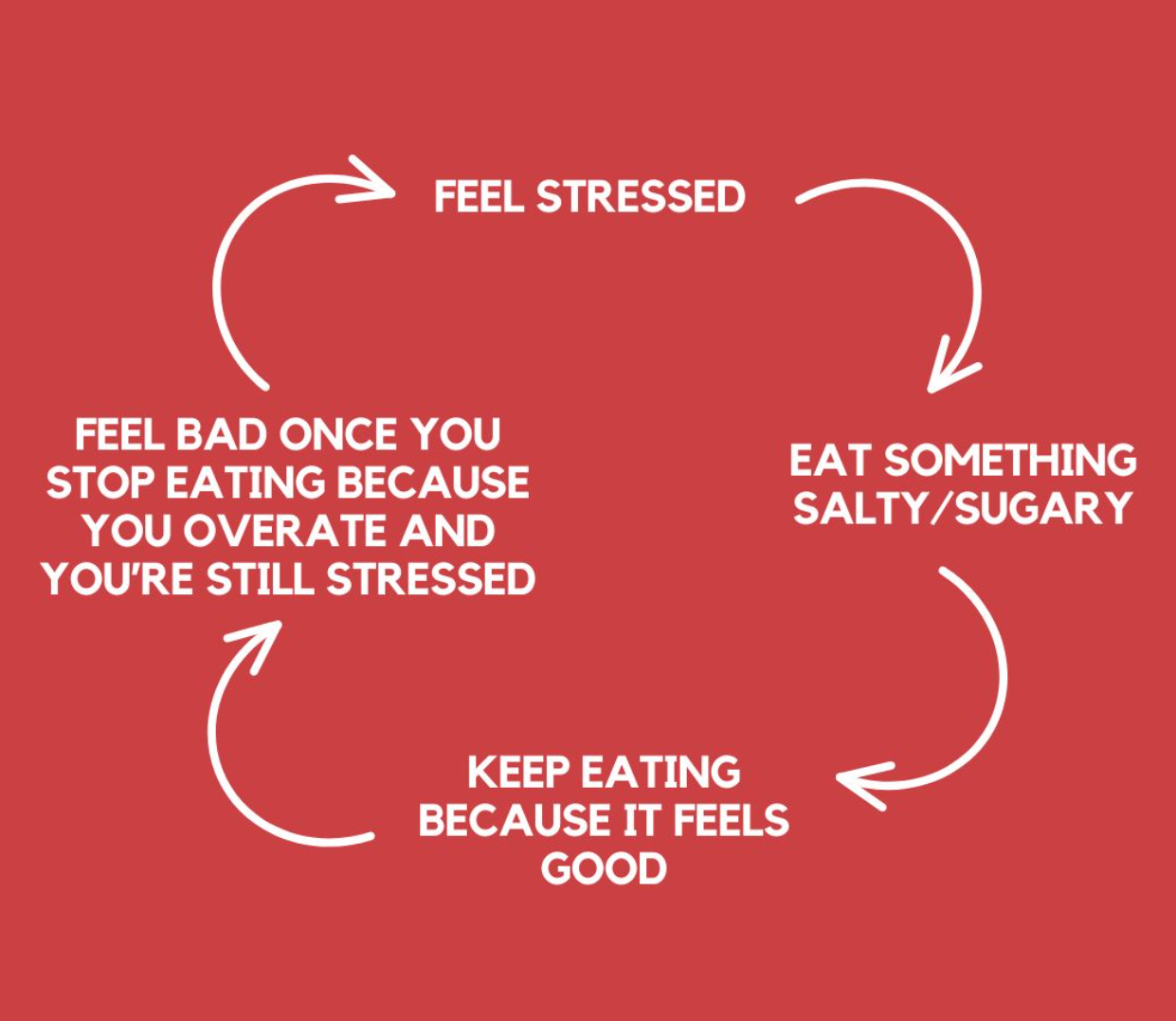

In addition, self-regulation depletes over time (often described in older studies as “ego depletion”) and can be undermined by repeated temptations. When we’re exposed to frequent “eat now” cues, our cognitive resources become strained. As emphasised by Dohle et al, the executive functions responsible for inhibition and decision making are integral to the self-regulation of eating, but these executive functions are neither boundless nor invulnerable. Emotional stress, for instance, can reduce our capacity to utilise them effectively. That’s why many of us experience a lapse, grabbing a chocolate bar, especially at the end of a tense day.

Behavioural Economics and Nudges

Roberto and Kawachi argue for rethinking public health interventions based on insights from psychology and behavioural economics. Rather than assuming individuals always make rational, self-interested choices, a nudge capitalises on behavioural tendencies. Setting healthy side options as the default on a menu, for instance, or placing fruits at eye level in a cafeteria, can meaningfully boost the likelihood of healthier decisions.

Nudges are often most effective when they’re subtle. Their success depends on preserving freedom of choice while guiding it. For example, if an office cafeteria automatically serves water with meals instead of sugary drinks, employees can still pick up a soda if they truly desire, but the design of the environment encourages the healthier choice. In essence, these interventions reduce reliance on self-control by systematically offloading part of the decision-making process onto “choice architecture.”

Beyond Willpower A Broader Decision-Making Framework

Tomiyama points out that focusing too heavily on self-control can overlook important alternative pathways to healthy eating. These alternative pathways may include identity-based eating (thinking of oneself as “I’m a person who loves vegetables”), macro-level environmental restructuring (limiting junk-food adverts), or building an emotional support network to ride out stress without seeking comfort in food. Each of these can be folded into a broader decision-making model, one that accounts for habit formation, socio-environmental cues, and personal identity.

Habit Formation: Over time, repeating small actions can form automatic patterns that don’t rely on daily self-regulatory battles. If you consistently stock your fridge with fruits and remove sugary snacks from view, you gradually create new “defaults” for your future self.

Socio-Environmental Cues: While personal habits matter, so do family conventions, workplace norms, and cultural traditions that heavily influence when, what, and how we eat.

Identity and Values: People who see healthy eating as congruent with a cherished self-image or strongly held value (like caring for the planet) tend to maintain it more consistently, even in challenging scenarios.

Neuroscience and Self-Regulation of Appetite

Cutting-edge neuroscience also underscores how the brain integrates signals (metabolic, hormonal, emotional) as we decide what and how much to eat. Rangel documents how brain regions involved in reward valuation, impulse control, and habit formation work together, or occasionally clash, to shape dietary decisions. Meanwhile, if we’re in a negative mood, some of these same brain circuits “light up” in ways that dampen inhibitory control.

Stoeckel et al. highlight that self-regulation is compromised when the neural balance between motivation-reward circuits and executive-control circuits leans too heavily toward hedonic impulse. Interestingly, changes in environment or habit can, over time, rewire these patterns. The more we succeed in a particular self-regulatory effort, say, consistently choosing a balanced plate, the more we reinforce neural circuitry that facilitates making the same choice next time.

Unique Challenges for Younger and Overweight Populations

Children and adolescents face additional hurdles for self-regulation. Bauer and Chuisano note that a young person’s environment, where sweet snacks might be freely accessible at home or sugary drinks widely advertised, significantly influences their ability to self-regulate. Teaching “intentional self-regulation” from an early age, including how to navigate peer pressure and question marketing messages, can promote healthier habits that extend into adulthood.

For overweight and obese adults, self-regulation can be hampered by multiple cycles of weight loss and regain, eroding confidence in one’s ability to sustain healthy habits. According to Reed et al. phenomena like “disinhibition” (a tendency to overeat in response to emotional or situational triggers) intensify. This underscores the importance of designing interventions that prioritise psychological support, emotional regulation, and structural changes, rather than depending on willpower alone.

Practical Strategies: Setting Ourselves Up for Success

What can we do, concretely, to strengthen self-regulation without feeling we engage in a daily struggle? Here are some actionable ideas derived from both Roberto and Kawachi (2014) [9], Tomiyama (2024) [1], and the broader literature:

Create Supportive Environments

• If you find it hard to resist crisps at night, avoid buying them in the first place. Stock up on more wholesome alternatives (e.g., nuts, air-popped popcorn) and keep them front-and-centre in your kitchen cupboards.

• Encourage workplaces or schools to adopt “healthier defaults” (like water instead of sugary drinks) and transparent nutritional signage to reduce reliance on personal willpower.Implement If-Then Plans

• Craft statements such as “If I’m feeling stressed at 3 p.m., I’ll take a walk before deciding on a snack.” This approach, known as implementation intentions, helps lessen impulsive decisions by specifying a contingency plan.Harness Social Influences

• Find a “healthy eating buddy” or group to share goals, meal ideas, and encouragement.

• If you have family or household members, try to set common ground rules, like frequenting fewer fast-food stops or cooking together once a week.Fortify Motivational “Why”

• Identify personal values that align with healthier eating, whether that’s environmental sustainability, improved fitness, or role-modelling for children.

• Revisit these values regularly, for instance, in a brief morning reflection, to keep them salient.Cultivate Mindful Eating Habits

• Pay attention to taste, texture, smells, and fullness levels. Eat slowly. Turn off distractions like TV or mobile devices during meals.

• Incorporate mindful check-ins: “Am I genuinely hungry, or am I bored or upset?” This helps reduce emotional or mindless snacking.Embrace Positive Failure Mindset

• Rather than seeing a dietary slip as a moral failure, view it as a data point. Learn from lapses. If you habitually snack at 11 p.m. out of stress, practise more comforting wind-down routines earlier in the evening.

Addressing Larger Systems: Policy and Societal Change

While individual action plays an important role, Tomiyama (2024) [1] and Roberto and Kawachi (2014) [9] both stress that large-scale improvements in population health demand structural reforms. Public policy interventions could limit misleading marketing, mandate clearer labelling, or restructure default meal options in schools and workplaces. Over-reliance on individuals “just trying harder” can be both unfair and ineffective in the face of ubiquitous, ultra-processed foods and aggressive advertising campaigns.

Behavioural economics–informed policies (e.g., better “choice architecture” in supermarkets) have shown promise. Encouraging supermarkets to place produce in high-traffic areas or implementing “shelf tags” that highlight nutrient-dense items can shift consumption patterns across entire communities. It’s easier to self-regulate when our environment aligns with, rather than undermines, our efforts.

Final Words

Efforts to manage our eating, particularly in a world saturated with calorie-rich, easily accessible foods , require a nuanced blend of self-regulation, environmental support, and public policy initiatives. Relying on sheer willpower alone ignores the evidence that food decision-making is governed by multiple psychological and physiological processes, as well as powerful contextual cues.

Recognising that self-control is only one piece of the puzzle, we can pivot towards broader strategies: redesign food environments to reduce reliance on constant restraint, capitalise on small nudges that encourage healthier defaults, and maintain a compassionate mindset toward our own lapses. Integrating identity, emotional regulation, and social norms into our approach can further bolster resilience.

As the science suggests, real change happens when personal actions, cultural shifts, and policy moves all reinforce each other. Whether you’re an individual looking to improve your diet or a policymaker seeking to enhance public health outcomes, it’s time to embrace the complexity of self-regulation and design solutions that truly empower better eating choices , no endless battles with willpower required.